Keywords: Modernism, Hilma af Klint, Theosophy, Abstract Art, Spiritualism, Wassily Kandinsky, Canon Formation, Piet Mondrian

For decades, the history of Modern Art has been narrated as a linear progression of rational inquiry—a steady march from Realism to Impressionism, culminating in the pure, intellectual geometry of Abstraction. This formalist history, championed by institutions such as the Museum of Modern Art in the mid-20th century, framed Modernism as a secular and quasi-scientific dismantling of the visual world. Recent scholarship and major retrospectives, however, have decisively unsettled this narrative. We now recognize that the origins of abstraction lie not in rational formalism alone, but in esoteric, occult, and spiritual systems of thought. The invention of non-objective art was fundamentally a spiritual project: an attempt to visualize invisible forces believed to structure reality itself.

The canonical account of Modernism—famously visualized in Alfred Barr’s 1936 flowchart—presents abstraction as the logical endpoint of European art history. In this model, Cézanne fractured the visible world into planes, Picasso dismantled it further, and Mondrian resolved it into purified geometry. This teleological narrative served a specific cultural function. It legitimized Modern art as serious, masculine, and intellectually rigorous, distancing it from associations with mysticism, ornament, or the irrational.

Such purification was not accidental. It required the active suppression of artists’ stated motivations. By removing the esoteric core of Modernism, art historians constructed a secular mythology—one that fundamentally misread the works it claimed to explain. The exclusion of spiritual intent was not merely an oversight but a structural necessity for the consolidation of High Modernism. Critics emphasized flatness, autonomy, and medium specificity while ignoring extensive writings on vibration, cosmic order, and the soul.

This secular bias produced a lasting blind spot. It obscured figures who did not conform to the image of the solitary, rational male genius, particularly artists who understood themselves as conduits rather than authors. The recovery of these suppressed motivations forces a reassessment of Modernism itself: not as a rejection of meaning, but as an urgent search for it within a rapidly secularizing world.

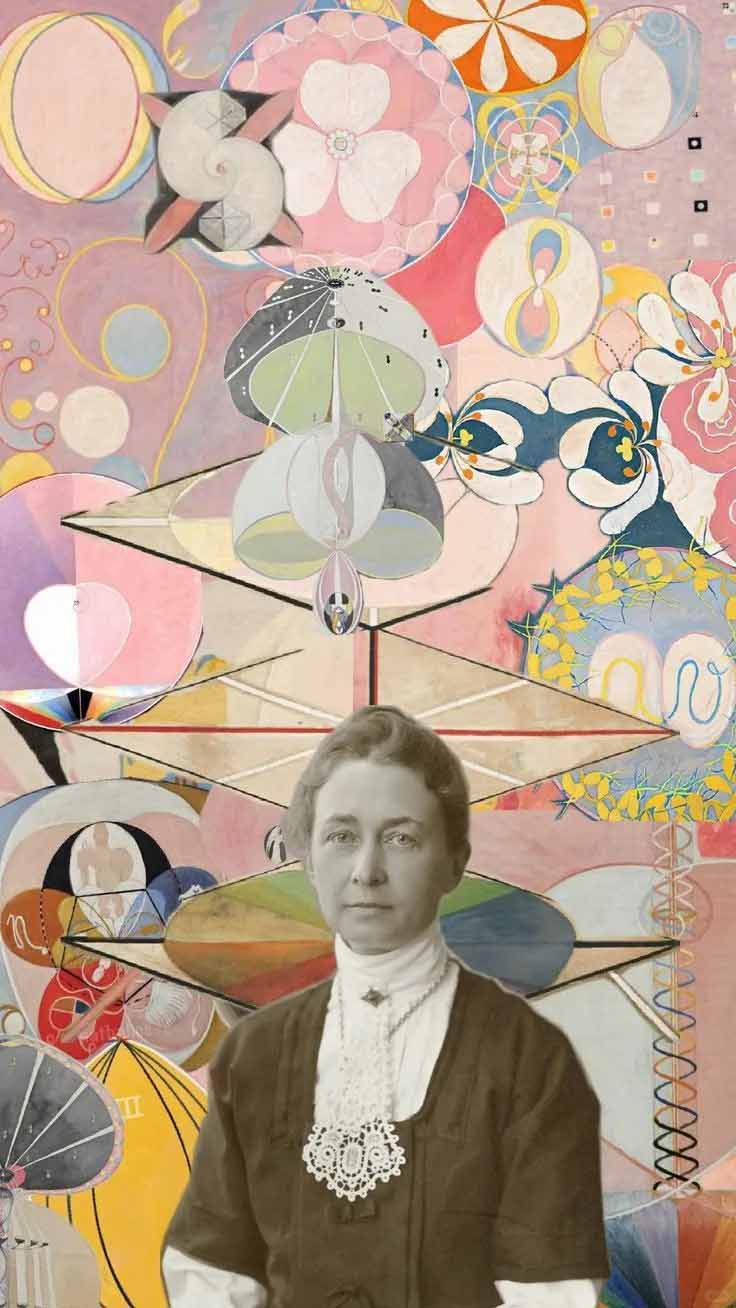

The most disruptive challenge to the established canon arrived with the late recognition of Hilma af Klint. Years before Kandinsky theorized abstraction or Malevich reduced painting to a black square, af Klint produced monumental, fully abstract works in Stockholm. Working within a spiritualist collective known as The Five, she understood her practice as mediumistic, claiming that her paintings were commissioned by non-material intelligences.

Works such as The Ten Largest (1907) employ spirals, chromatic codes, and botanical geometries to diagram spiritual evolution. These paintings predate the canonical “invention” of abstraction, yet they were excluded not only because af Klint was a woman, but because her method—spiritual transmission—was incompatible with the Modernist brand of rational autonomy.

Her marginalization exposes institutional discomfort with overt occult belief. Whereas Surrealist automatism could later be reframed as psychological experimentation, af Klint’s literal engagement with spirits was dismissed as eccentric or amateur. Yet her visual system is neither naïve nor derivative. She did not abstract from nature in the conventional sense; she visualized unseen structures directly. Her Temple Series was conceived not for exhibition but for a spiral architecture designed to facilitate spiritual ascent. Af Klint’s oeuvre demonstrates that early abstraction was not a minimalist reduction of form, but a maximalist attempt to map invisible cosmologies.

To understand the formal language of early abstraction—primary colors, grids, intersecting planes—one must consider Theosophy. This esoteric movement proposed that geometry and color functioned as universal spiritual languages, capable of revealing hidden realities. Far from being marginal, Theosophy constituted a shared intellectual framework for many avant-garde artists.

Mondrian’s grids did not emerge solely from aesthetic refinement. They articulated a theosophical worldview in which vertical and horizontal lines embodied the equilibrium of opposing forces: spirit and matter, masculine and feminine, dynamic and static. Neoplasticism functioned as a visual theology, intended to induce contemplative balance rather than merely please the eye.

Kandinsky’s abstraction likewise stemmed from spiritual conviction. Influenced by theories of thought-forms and synesthetic vibration, he sought to create an art that bypassed representation and resonated directly with the soul. Even Suprematism, often framed as radical negation, drew on mystical ideas of zero-point existence. This shared visual language was not a denial of formal evolution, but a reinterpretation of form through esoteric doctrine.

Decades before Modernism’s supposed rupture, Georgiana Houghton produced complex abstract watercolors under trance conditions. Created in the 1860s and 1870s, her works were attributed to spirit guidance rather than individual authorship. When exhibited in London in 1871, they confounded critics precisely because they defied existing categories of art.

Houghton’s practice anticipates Surrealist automatism while challenging the very notion of artistic intention. Here, the artist is not an expressive genius but a receiver of transmission. Her work suggests that abstraction emerged not first in avant-garde cafés, but in domestic spiritualist spaces largely occupied by women.

The rediscovery of figures like Houghton and af Klint destabilizes both the geography and gender of Modernism. It reveals that abstraction’s early development occurred outside institutional visibility, among practitioners for whom spiritualism provided an alternative mode of authority. In this light, the modern aesthetic appears less as a formal revolution than as a spirit-driven one.

The portrayal of Modern Art as a triumph of secular rationality is a historical construction rather than a neutral account. Reintegrating the occult and spiritual motivations of early abstract artists transforms our understanding of Modernism. Abstraction was not simply a style; it was a technology of transcendence. The modern gallery’s white cube thus emerges as a secularized temple, built upon esoteric blueprints and the visions of long-silenced mediums.

Hi, I’m Philo, a Chinese artist passionate about blending traditional Asian art with contemporary expressions. Through Artphiloso, my artist website, I share my journey and creations—from figurative painting and figure painting to floral oil painting and painting on landscape. You'll also find ideas for home decorating with paint and more.

1. Why was the spiritual aspect of Modern Art ignored for so long?

Mid-20th-century critics and curators wanted to establish Modern Art as a serious, progressive, and autonomous discipline. They feared that associating abstraction with occult belief would make it appear irrational or unscientific, and therefore emphasized formal qualities while downplaying mystical intent.

2. What is Theosophy and why was it so influential to artists?

Theosophy blended Eastern philosophy with Western mysticism and science, proposing that hidden realities could be accessed through symbols, color, and geometry—offering artists a framework for non-representational art.

3. Did Hilma af Klint know Kandinsky or Mondrian?

There is no evidence they met. They worked independently but were influenced by similar spiritual movements. Af Klint kept her work private, contributing to her historical exclusion.

4. Is Abstract Art always spiritual?

No. While early abstraction was largely spiritually motivated, later movements such as Minimalism rejected metaphysical interpretation.

5. How does this rewrite Art History?

It recenters marginalized figures and reframes abstraction not as pure design, but as a visual system shaped by spiritual belief.